Gotta make sure I put the “Sir” before Andras Schiff in the title because damn, that performance sure deserves some deference and respect!

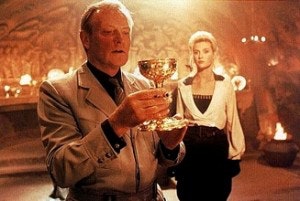

As piano students, I think we’re kind of brought up with the idea that the last three piano sonatas of Beethoven are on the Holy Grail level of the standard canon. They’re not untouchable; far from it, you hear them echoing through every corridor of conservatoires. But like the Holy Grail in “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade”, they can easily be mistaken for elegant, jewellery-studded chalices, and if you drink from them you DIE! For what is most transcendent, what is closest to the heart of the truth, what may perhaps open the door to immortality is not always the most glamourous.

I, for one, fell in love with Beethoven’s op 109 because it was so beautiful. The opening was so lyrical, and at the climax you just want to pour your heart out as your hands stretch to the ends of the keyboard! But is that all Beethoven is as he nears the end of his life? Is that all he amounts to? A passionate outburst from an old, graying man, a return to chorales, fugues and all that Baroque jazz? I don’t think so. One cannot listen to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, his Tempest or Appassionata Sonata and believe the last three sonatas to be the culmination of expression on that trajectory. Like the British government on the issue of the A-levels recently (that is the where I draw the line in my analogy), Beethoven’s mode of expression makes a complete U-Turn in his final three piano sonatas.

Luckily, you will not die if you play late Beethoven majestically or sentimentally, but I think hearing Andras Schiff play reminded me that no matter how many Chopin etudes I can play flawlessly (I am currently struggling to play just the one), Beethoven will always be the master who generated centuries of scholarly debate and pianistic study. No, all these studies are not conspiracy theories to glorify a common man. As my teacher Noriko Ogawa says–and gesticulates dramatically: Beethoven likes to dig deep.

In short, I was put back in my place by Sir Andras Schiff.

To be very honest with you, I would have probably opted out of Andras Schiff’s recording of op 109 if I had heard it on Apple Music. I’d choose a performance more comfortable to listen to, more suitable to my ears. Maybe someone like Brendel (no offence, Alfred!). The opening of op 109 is so sweet, so flowing, so lyrical…yet Andras Schiff plays it with minimum pedal; indeed, he plays everything with minimum pedal. The arpeggios of op 110 he plays with almost no pedal, accenting at irregular points, making the music sound fragmented and angular rather than seamlessly flowing.

Schiff also does not partake in cheesy, Romantic sentiment. He does not create a huge sound when the first movement theme of op 109 reaches a climactic point as the melody and the bass reach the (relatively, for Beethoven’s time) registral extremes of the piano. When Schiff plays, the melody in the right hand is always singing, always cantabile, and never appearing to reach towards the heavens in a defiant manner. In the “Prestissimo” of op 109, he does not play at breakneck speed to demonstrate virtuosity. Instead, he focuses on the polyphonic texture of the movement. Octave chords in the left hand are also melodic material for Schiff; they are never simply there to create grand, booming sounds. He brings out so many hidden voices I’ve never heard before, I gradually begin to lose myself in his unique sound world. In fact, sometimes he is so intent on bringing out voices that he chooses to omit other notes in a chord. I think it’s got something to do with Schiff’s absolute mastery of Bach. To start the concert, he played Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in E major from Book II of the Well-Tempered Clavier without using any pedal, and you can definitely see his method of playing Bach’s polyphony when he plays the late Beethoven sonatas.

On that (polyphonic) note, I think there’s something to be said about Beethoven’s use of the fugue in his last three piano sonatas. Fugues are usually very satisfying to listen to; as the same subject is repeated, transformed or transposed along the staves, wondrous harmonies are created. There is something grand and massive about the coming together of many voices, but I think Beethoven uses fugue in his late works in a much more different manner to Bach. Beethoven’s fugal subjects are not well-calculated, unlike Bach; some of them are mere motivic cells. Nor are his fugues mathematically perfect; they sometimes dissipate quickly into homophony. Some critics have said that Beethoven was never the writer of fugues that Bach was, but perhaps it was never his intention to emulate Bach. Andras Schiff envisions the fugal writing of Beethoven as fragmented. The fugal subject of the final movement of op 110 pops up everywhere, overlapping other answers, jutting out in an angular way, and Schiff really shows that in his playing. It is very chaotic in a way, but that’s the thing with Beethoven: his music, especially his late music, was never meant for easy listening.

Under the spell of Andras Schiff, the music seems to live precariously on the edge. No, that’s not right. I seem to live precariously on the edge. His playing is full of surprises and, having no idea what to expect, I can only be present and listen in the moment. That’s what I mean by being spellbound by his performance. Under his fingers (and Beethoven’s meticulous direction), convention is broken down. Arpeggiated chords that would normally sound like accompaniment becomes angular and jarring. Trills that are normally supposed to add an air of intensity to climactic moments suddenly become isolated; they are no longer a means of expression but an end in themselves. Lyrical phrases are interrupted by subito pianos and diminished cadences. I am reminded of a quote by famous philosopher Edward Said on Beethoven’s late music:

And so it goes in the late works, massive polyphonic writing of the most abstruse and difficult sort alternating with what [Theodor] Adorno calls ‘conventions’ that are often seemingly unmotivated rhetorical devices like trills, or appoggiaturas whose role in the work seems unintegrated into the structure

Edward Said, On Late Style

The general gist is that Beethoven’s late music is a jumble of everything, and amidst the chaos, conventions are stripped of their contexts. It is therefore completely natural to feel their unnaturalness, to be unsettled by Beethoven. In one of his characteristically dramatic, difficult-to-understand sentences, the famous German philosopher Theodor Adorno says of Beethoven’s late works:

The force of subjectivity in late works is the irascible gesture with which it leaves them. It bursts them asunder, not in order to express itself but, expressionlessly, to cast off the illusion of art

Theodor Adorno, Beethoven: The Philosophy of Music

Now I can’t make heads or tails of ANYTHING else Adorno writes, but this sentence I love! I don’t think I fully understand it yet, but it gets me thinking. It makes me think that the sense of individuality so strongly felt in Beethoven’s earlier works like his Fifth Symphony and his Appassionata sonata, one which has a sense of narrative, one which has a trajectory, a beginning and an ending, is cast aside in his late works. Instead, by breaking down his music into fragments, he “casts off the illusion of art”, as if to say his earlier mode of expressing subjectivity no longer suffices. The idea that there is a coherent self to be expressed through music is negated, and so what we are left with are floating fragments.

Now, before you start getting all depressed thinking that if Beethoven believed that there is no coherent self and art is an illusion and that life is meaningless then what hope is there for the common man, let me just say that I do not think Beethoven is being any less expressive in his late music. If anything, judging by how meticulously he marks his scores (even more so in his late works), I think it is by “casting off the illusion of art” that he achieves expression. The only way to come closest to the truth is by revealing all the artifices, and Beethoven does that by covering pages of music with sforzandos and marking his tremolos down to the hemidemisemiquaver, so that people who interpret his music will feel tripped up by a common scale or arpeggio. By being specific, Beethoven contradicts the natural tendencies of expression, and that is precisely his intention. Yes, Andras Schiff’s playing may at times sound awkward and unnatural, but consult the score and you’ll realize that his performance completely adheres to Beethoven’s instruction! Through listening to Schiff play, I am reminded that music was never made to serve man, to express himself, but that it is from unnatural artifices that music can create the illusion of man being greater than his destiny. In truly confronting his destiny, Beethoven seeks to strip all these musical artifices bare. That, perhaps, is the philosophy of his late music.

It is remarkable to observe that such a great man as Beethoven has left so much to posterity and yet we are still constantly in the process of discovering this greatness even when almost every piano student has a copy of his piano sonatas. The beauty of it is that Beethoven speaks to each person differently. There seems to be something of an unwritten rule in the world of institutional classical music that if you follow whatever Beethoven wrote on his score, you will be able to play Beethoven. That is a great simplification of the complexity of Beethoven’s music, but it is true that unlike many of his contemporaries, he has taken great pains to instruct future pianists he will never be able to meet on how to play his music. Still, what he leaves are not mere algorithms to plug into the keyboard, but a whole philosophical outlook that I must take time and patience to learn and understand. Some of his late music are actually pretty-hard-to-swallow pills, but they definitely ask some interesting questions if one takes the time to listen. Listening to Andras Schiff perform Beethoven’s final three piano sonatas was definitely one of those times.

Oh and also, I am glad I made a blog post about Beethoven before the year is over, seeing it is the 250th anniversary of the great composer’s birth. 2020 has been such a rubbish year, but I guess one thing we can be thankful for is that 250 years ago baby Ludwig was crying for his mother’s milk.

You can watch Sir Andras Schiff’s performance of Beethoven’s last three piano sonatas in the Wigmore Hall here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xd-sFoTXCIg&ab_channel=WigmoreHall

Leave a comment