Yes, I mean what else do you call someone who plays the celeste in an orchestra?

Exactly. A celestial. Cue Marvel theme song.

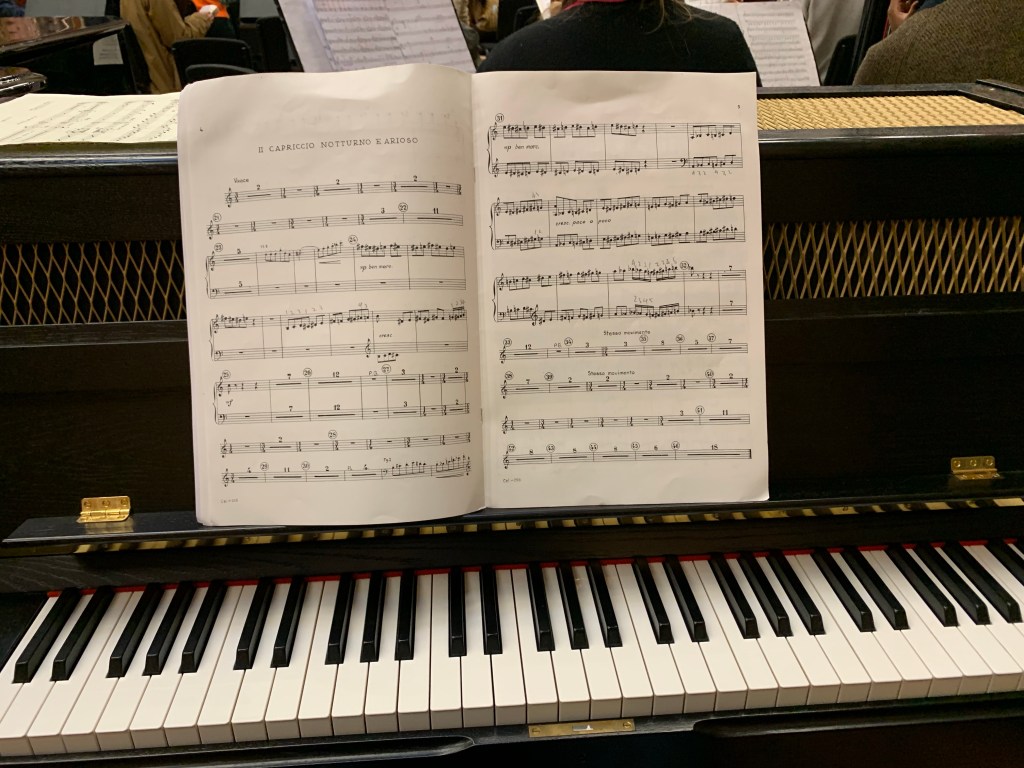

I was recently invited to play with the Guildhall Symphony Orchestra in the Lutoslawski Concerto for Orchestra, one of three pieces in an epic programme (the other pieces being Ravel’s Shéhérezade and Scriabin’s La Poeme de l’extase). This isn’t the first time I’ve played in an orchestra, but it’s certainly the first time I’ve played in one that operates like a professional orchestra–and obviously one that plays like a professional orchestra. It’s also the first time I have so little to do in an orchestra!

To give you an example, I only have one single note to play in the entire first movement. Yes, one single F sharp, which I hit for about a hundred crotchets, while the rest of the orchestra rages and dances around me. Having received the score and looked at the long hours of my timetable scheduled towards this orchestral project, I held nothing but the dread of sitting there in rehearsal doing nothing. Turns out this having nothing to do was not an invitation to practise stoic meditation in the face of cacophony (there’s a lot of noise in the Lutowslawski); I learned so much from observing the orchestra and the way they rehearse. Here are some of my observations:

- Preparing for orchestra takes a lot of time, the rewards of which are not always satisfying to the soloistic ego

I’ve always kind of seen the string section as one in an orchestra. I mean, they are supposed to sound like one. The best string sections in professional orchestras are ones that sound like one big wave rather than many individual instruments. When I was playing flute in the secondary school orchestra, the strings were a foreign section who seemed to have their shit together, while the wind section was a competing mass of soloistic egos. But this time, observing from the sidelines as a pulse-beating celestial, I realized how much effort must’ve gone to practice for string players. The Lutowslawski is notoriously difficult for all instruments (except mine) and I was lucky enough to be free enough during rehearsals in order to witness the progress towards performance standards by the whole orchestra. Everyone had to really play their part in order to create the effect of order among chaos which I think generally sums up the Lutoslawski concerto. Not only are the string parts extremely difficult, one small slip from one single member can cause the disintegration of the illusion of order among chaos, and descend into pure chaos. I’m not really used to practising hard in order to blend in, which is why I admire the efforts everyone put in in order to hold everything together. It’s also why I suffered a few humiliations during rehearsal when I was busy focusing on texting and couldn’t come in to hit the only note I had to play for the entire movement.

2. The credit given to the conductor is justifiable

In the first two rehearsals we were assigned an assistant conductor; during the week of the concert the actual conductor for our concert, Roberto Gonzalez-Monjas, took to the podium. I was amazed at realizing how much the conductor actually has to worry about when conducting. When we see a conductor in performance, we see him waving his arms about at a pace usually faster than the orchestra, and so it feels as if he is minding his own business while the orchestra is minding its own. In reality, the conductor has to juggle everything: he has to stay ahead of the orchestra with his pulse, taking into account the instruments that normally sound a little bit later than the downbeat; he has to hold the sections together, making sure the orchestra retains its own inner pulse; all the while he has to prepare for what is to come, and indicate exactly what he wants from the orchestra! In a sense, the conductor must juggle present and future simultaneously. I have conducted orchestras myself, but because it was an amateur orchestra all I had to–and could–worry about was making sure everything stuck together, albeit not seamlessly, for the actual performance. But Roberto had to know the score inside-out in order to make sure the orchestra not only sticks together, but actually delivers a convincing musical performance. The biggest risk for the conductor is that he does not have actual control of the music: the players are the ones with that power. He can’t force me if I refuse to hit the right note on stage or manage to somehow remain distracted during the performance. Unlike a solo pianist, who has the power to control the music he produces, the conductor takes a leap of faith in every performance. And so he should also be given the greatest credit after each successful performance.

3. Playing in an orchestra is not as easy as you think

For a solo pianist, I definitely learned some new skills working in an orchestra as a percussion player. I am a “soloist” in that I am in the only one playing my part, so I must take full responsibility of what I play. There’s no one to cover me, and even though I play a very simple part, I am also very exposed, especially in the first movement of the Lutoslawski. What was most challenging for me was the fact that I had to resist the urge of following the conductor’s beat. I play on every crotchet beat, so it was very easy for me to just play according to Roberto’s pulse.

But I could not. I must follow the orchestra. And so while looking at Roberto give one pulse my ear must remain loyal to the pulse set by the wind section. At first this resulted in a warring conflict within my pscyhe. Being relatively untrained in the art of listening to others, and even more amateurish of providing a pulse (we often resort to the metronome for that service) it took me a long time to get used to it. But when I eventually did so, through ear-straining attention and a disproportionate amount of focus, I managed to find an inner pulse to settle onto that somehow worked against the beat set by Roberto. It was then that I felt more like part of an orchestra rather than a soloist contractor playing a toy piano alongside a fully professional orchestra.

Who knew banging out F-sharp crotchet beats would be so difficult?

Leave a comment