A day of nationwide rail strikes did not stop a healthy number of people from flocking to King’s Place to attend the third concert of the London Piano Festival, in which Russian pianist Katya Apekisheva and Japanese pianist Noriko Ogawa shared the stage in presenting the preludes of two very different composers from the 20th century: Dmitri Shostakovich and Claude Debussy.

Watching the concert, I realized the programming of preludes is a great choice for an afternoon concert: despite being short pieces, they provide crystal-clear glimpses into the creative spirit of the composers. Played together as sets, they give the audience short and sweet musical vignettes to bring home in their memories as inspirational souvenirs.

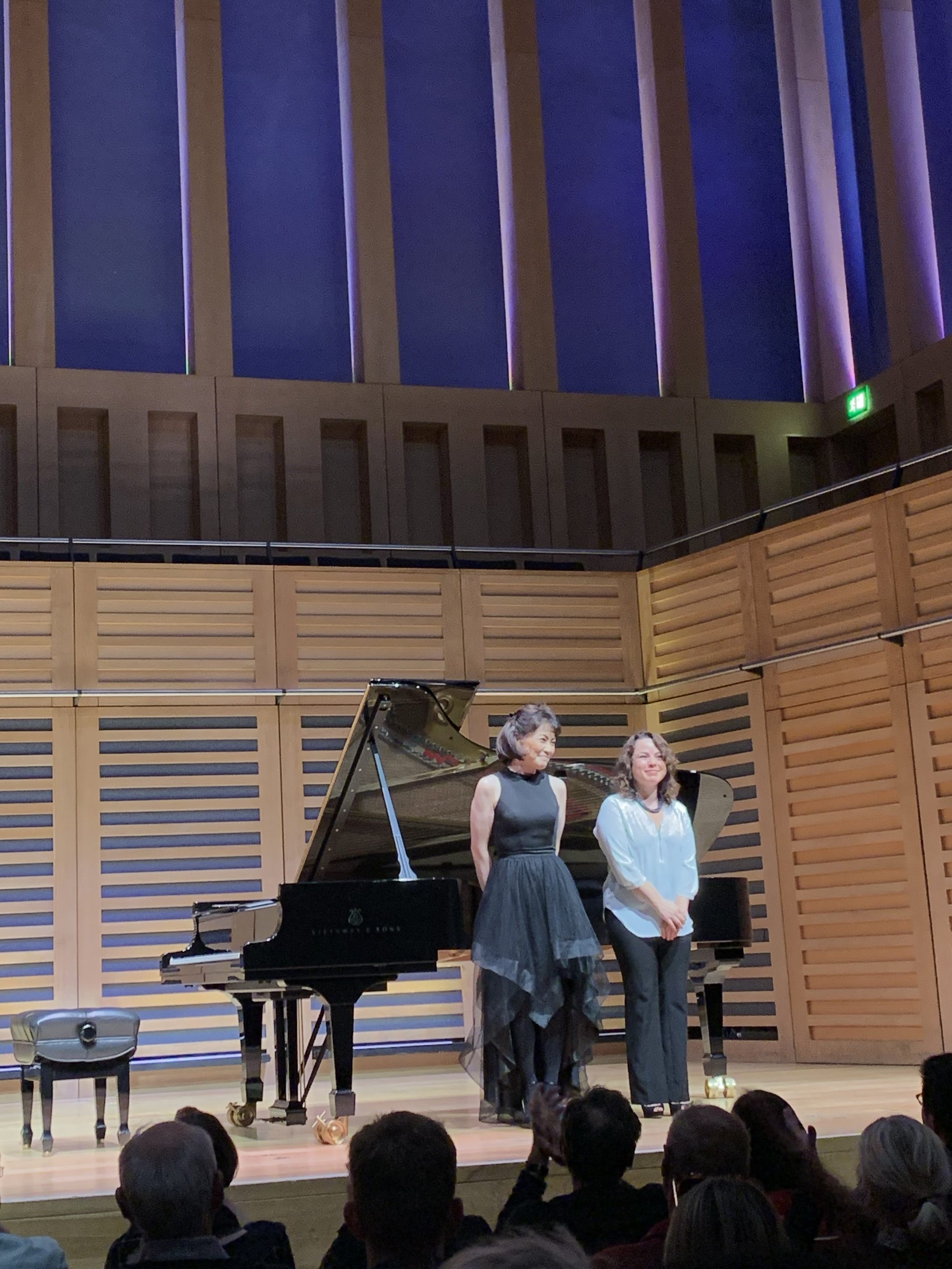

The presentation of two very different composers by two very different pianists, performing successively without interval, also gave me food for thought on how approaches to pianism shape a performance just as much as approaches to setting sound on paper.

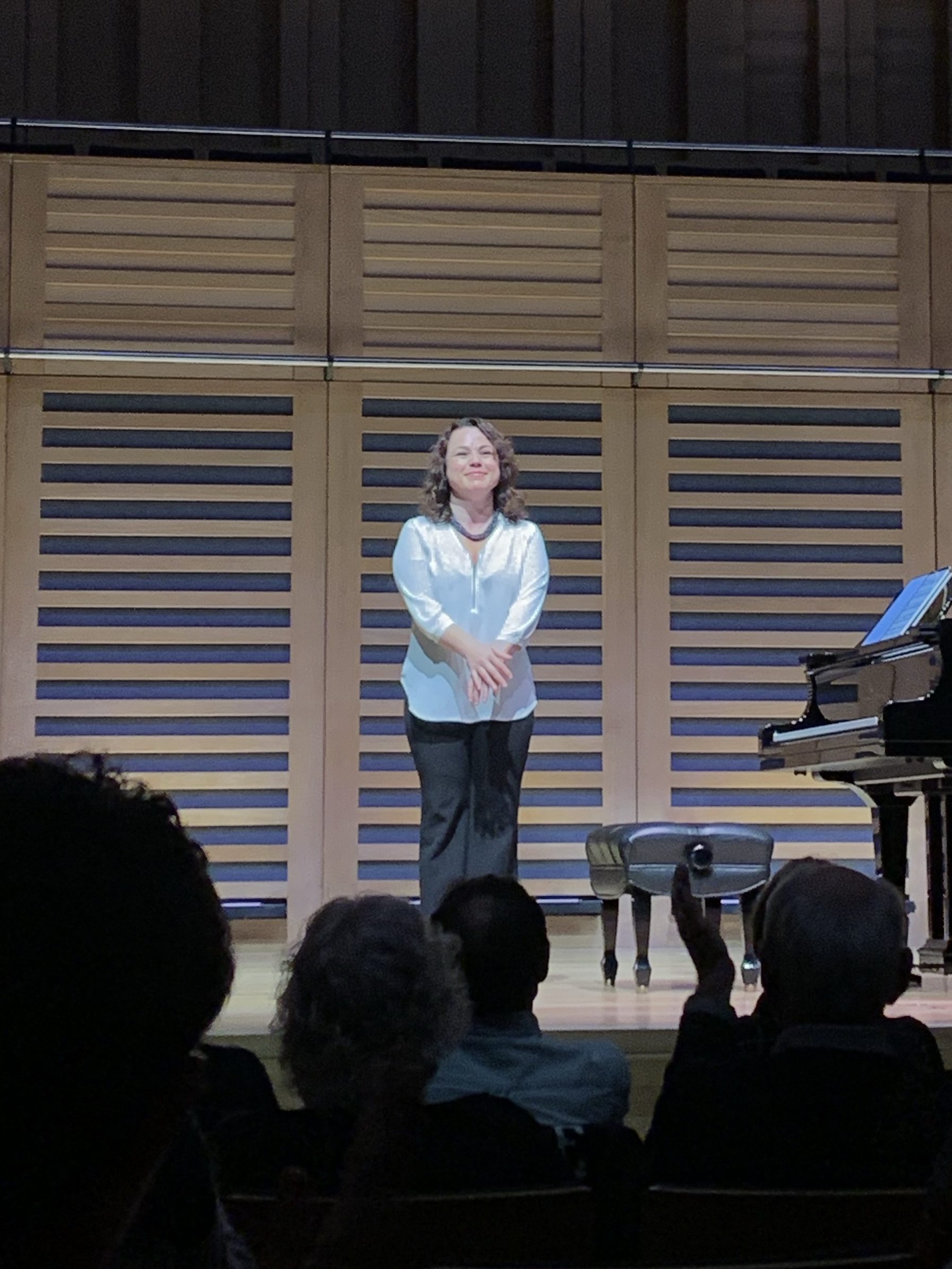

Katya Apekisheva opened the afternoon with Shostakovich’s 24 preludes, op. 34. Like most composers who composed sets of 24 preludes, they follow the circle of fifths, with one prelude in each major and minor key. As a set, it is a wide palette of moods, from the crassly sarcastic (no. 15 in D flat major or no. 24 in D minor) to the melancholic (no. 1 in C major) to the intensely tragic (no. 14 in E flat minor).

Katya played through the 24 preludes without much of a pause, settling into vastly different moods in a flash–the change from the melancholic no. 1 to the quick and agile no. 2 being one example–and taking us on a whirlwind tour with her, using her iPad only as an emergency aid; she did not look up much except to turn the pages, and the music seemed to flow very naturally from her fingertips.

Her playing was extremely beautiful. I caught a glimpse of it last night at the Schubertiade, but this afternoon, alone on stage, she showed us the potential of her versatile touch, which can at times be very deep and sonorous–as she demonstrated when she played the E flat minor prelude–and so exquisitely soft I had to strain to hear the final note of the beautiful A flat major prelude that reminded me very much of Chopin. I cherished this fragility in her playing a lot, because it represented the fragility of emotions that can be extracted out of Shostakovich’s music.

Nor did she hold back when it came to technically daunting passages; Katya’s fingers flew across the keyboard in the hair–raising fifth prelude in D major, showing no sign of fear. It was the naturalness of Katya’s playing that revealed to me the creative genius of Shostakovich–at times very original, at others self-referencing (the repeated crotchet motif in the third prelude in G major is used again in the fugue of the last prelude and fugue in D minor, op. 87) or even parodying other composers (I definitely heard a little bit of Chopin’s final prelude in Shostakovich’s final one, both in the same key!).

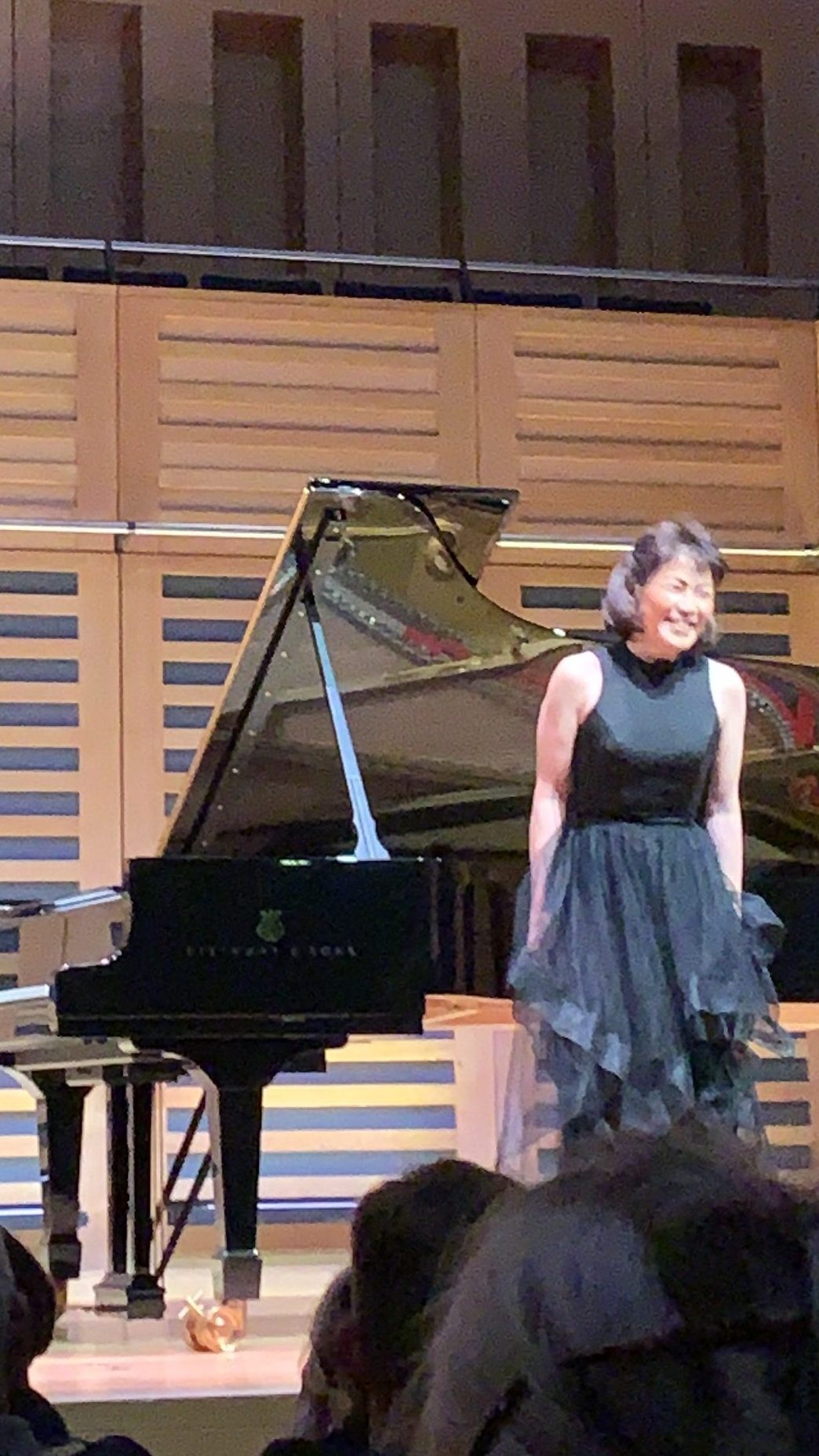

It was only when Noriko took the stage–after the rightly deserved enthusiastic applause for Katya–and set the piano bench much higher that I realized how low Katya sat at the piano. As Noriko played, I realized how differently the two pianists used their body; Katya sinks low and deep into the keys, following the music with the movement of her whole body, while Noriko leans over the keyboard in a fairly fixed position, using her shoulders to produce a big sound and her fingers strengthened by years of practice to evince a bright clarity from the Steinway.

At the piano, Noriko wore the intent look of a potter carefully shaping her clay. Indeed, she gradually molds each prelude by Debussy into shape, carefully layering one idea on top of another, revealing to us her unique vision of Debussyan architecture. In no other prelude than “Voiles” (Veils) was this more clearly demonstrated.

Unlike the naturalness of Katya’s playing, I got the sense that everything was carefully planned out in Noriko’s performance, down to the strength required for a certain note and the length of each silence.

The more I listened to her play, the more I saw the virtue in such careful consideration in presenting a piece of music, especially when applied to Debussy’s preludes. The absolutely equal and precise repeating semiquaver patterns, as in “La vent dans la plaine”, provided great pleasure to the listener in their perfection, and drew us in as Noriko revealed the infinite textures Debussy’s music provides.

The precise calculation of silence also commanded our attention; “Des pas sur la neige” was arresting, the silence palpable as we held our breaths, not wanting to miss a thing.

Virtue lay not only in Noriko’s commitment to absolute precision and clarity, but also in the relentlessly massive sound she created, as in “Ce qu’a vu le vent d’ouest” (“what the west wind saw”), where waves of sound crashed against us without mercy. Her big sound, together with meticulously calculated timings, took on a grand and religious quality in “La cathédrale engloutie” (“the sunken cathedral”), which gave me goosebumps. Without noticing it, I had lifted my chin towards the ceiling.

Leave a comment