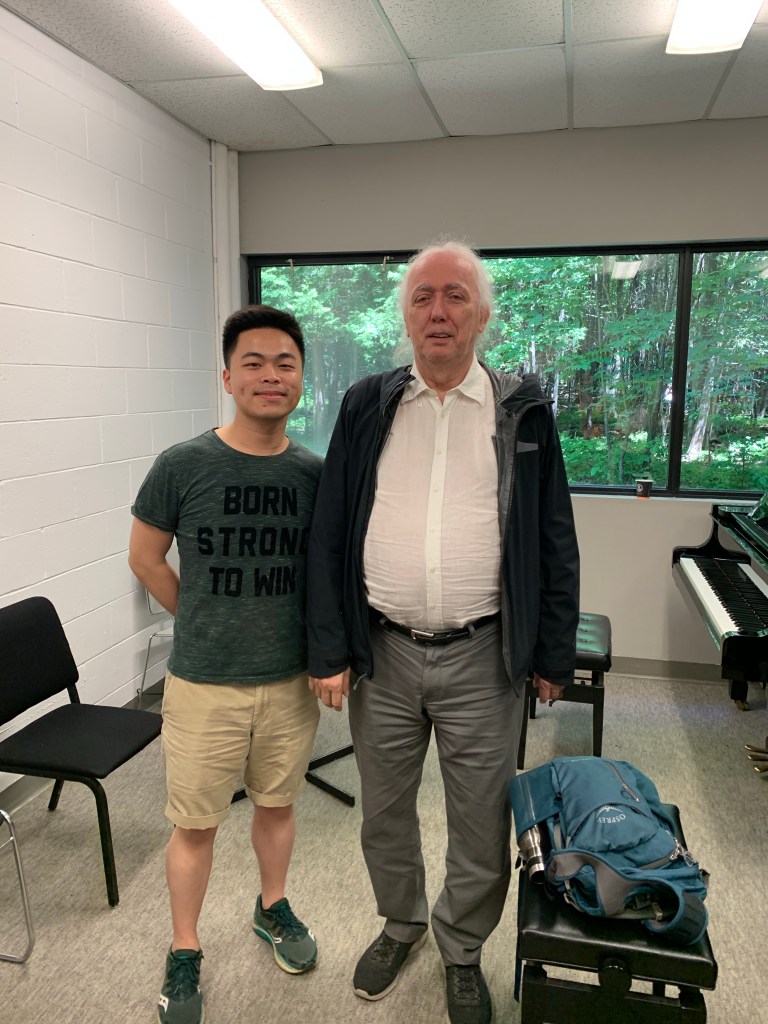

Even though there were only three piano professors at Orford Musique during the first week, it took me almost the whole week to identify the great André Laplante.

Picture a great pianist, whose name has reached the far corners of the world, whose recordings of Liszt has attained legendary status; the first ever Canadian to win the Tchaikovsky Competition back in ’78 and to make it onto the international stage, a pioneer paving the way for the next three generations of Canadian classical musicians. Now picture an old white man you would find in the pub on a Tuesday morning, having his fourth pint of Guinness and relating another old anecdote in slurred speech to the annoyed bartender polishing glasses. The latter would get you closer to the image of André Laplante. The truly great things about him were his height and his belly.

The first time I properly talked to him was on Saturday evening, when I was feeling rather moody after seeing all the Orford first-weekers leave. Sitting down at the cafeteria with a whole group of us pianists–quite a few of them were from his studio the week before–he asked where I was from. London, I replied.

Oh, yeah, I’ve been there a few times, he replied with a bored look, not quite sure how to continue the conversation. Nothing much happens there, he trailed off.

It took me a while to realize there had been a misunderstanding. Oh no, I meant the other one, the one in England! I came to my own rescue. Immediately his eyes lit up, he said why didn’t I say so before. It honestly hadn’t crossed my mind that here, across the Atlantic, people would associate London with a dreary small town in the middle of Ontario. I should have known better. I believe that it was from that point onwards that André found me interesting to talk at. Yes, talk at, because with pianists at that age it’s really better to goad them on to spill their stories than to tell them about yourself. So I got to hear André’s stories about Terence Judd taking him to tea at Fortnum and Mason’s, witnessing drunk Scottish men bathing themselves in the fountain of Trafalgar Square, being laughed at by British policemen when you pronounced Leicester Square as “Ly-ses-ter” Square. André seemed delighted to no end by having found a companion who could relate to his English adventures.

The flip-side was that from then on, André seemed to think I was some sort of alcoholic. Whenever there was talk of drink and pub, he would turn to me with a knowing wink. To be sure, I let it play on. If the great André Laplante takes an interest in you, you wouldn’t throw it all out the window. To my slight embarrassment, however, I began demonstrating–fairly exaggeratedly–a Cockney accent, something which seemed to delight André, but would not have gained me quite an appreciative audience back in England. I suppose just as there are ways the English see the Canadians, so there are ways the Canadians see the English. Either way, I got off to a good start with André Laplante, even if that meant having to sell my soul.

My second week at Orford Musique was a lot more intense than the first. The “studio” cultures of Jean Saulnier and André Laplante were totally different. With Jean, lessons felt more like private consultations, so the other students felt more at ease to drop in once in a while and leave to practise whenever they wanted to. I had much more time in the first week to practise than the second (which was good, as I needed the practice time for the Barber!). André conducts a more regimented schedule which consisted of one private lesson with one student in the morning followed by a masterclass with two students in the afternoon. Yes, he would only see three students in a day. His reputation for giving long classes had preceded him (his studio always came in last for dinner during the first week) so I had anticipated its intensity, yet the contrast between my week with Jean and this week still came as a massive shock, and nothing prepared me for a three-hour public masterclass with André Laplante.

It was obvious that I would bring the Liszt Sonata to André; his recording of the piece is perhaps the most famous one (top search on YouTube). I spent the whole weekend reviving the piece, which I had dropped after performing it (quite terribly) two months prior. I volunteered to play it at the public masterclass on Monday afternoon; it was a strategic move, because I needed as much time as I could to work on what he changed during the lesson.

André didn’t let me get to the end of the Sonata. That was expected, since the whole thing was half an hour long. He stopped me before I got to the end of the first movement. We worked on the first page alone, with the infamous, ambiguous opening, for about half an hour. Think vertically there, he said, referring to the first bar; think horizontally there, referring to the next two bars. Stop playing the notes, sing it! For him, every note was part of a phrase, and every phrase was part of a movement of the arms. He then hit me with one of his many iconic phrases: stop being a pianist; you have the means to be a good pianist (yes, he really likes to use the word “means”), but for God’s sake you have to stop trying to play the notes. When André demonstrated, I clearly saw what he meant. He could play everything perfectly and at quite a ferocious tempo, but listening to it, you did not marvel at its perfection, but rather at the force of expression clearly driving the playing. Phrase, phrase phrase! Phrase everything! There is always one note towards which the phrase goes; go for that note! He would repeat many of these short adages throughout the lesson–and in fact, throughout the week–which might seem very simple and obvious in the beginning, but in fact when applied to my playing would transform it drastically. Once he found something unnatural in my playing, something which did not respect the law of phrasing, he would latch onto it and not let go–like a dog holding a bone–making me play the passage over and over again until I got it right or he could tell that I understood what he was talking about. He made me repeat the famous octave passage near the beginning for God knows how many times until I was totally drained, and still we would continue. Playing the Liszt Sonata was already a test of endurance in itself; working on it with André was a marathon run (quite literally, since the lesson lasted about the time it takes a professional athlete to run a marathon).

By the time we finished it was 4pm. I felt bad for all the students in the audience, but they didn’t seem to mind. Apparently some have had their fair share of endurance training the week before, both on and offstage. I was physically exhausted. It was probably one of the most intense lessons I’ve ever had, but the intensity felt different from the one I had with Jean Saulnier the week before. I didn’t feel overwhelmed by the things I had to change (mostly fingerings); André was very specific with what he wanted so I knew exactly what I needed to correct. When the physical tiredness left me (that took a while!) and my mind was clearer to process all that had happened during the lesson, I was left with the impression of André breathing down my neck or whispering specific ways of playing certain passages when I started practising again. Even a week later, when I performed the Liszt Sonata in public back in London, I could hear André shout “Phrase it, don’t just play it!” when I got to the nasty fugue in the middle.

But his instructions were never intimidating. He never said such-and-such passage is really difficult; practise it loads or you’ll never get it right. Rather, once I got used to his idea of phrasing everything, and reoriented my practice in that direction, even the most technically tricky passages became do-able! Once I started thinking about those passages as “phraseable phrases”, applying the right tension and release as I would to a sing-able musical phrase, my fingers naturally glided to the right position. The more I practised the Liszt Sonata that way, the more I realized how much Liszt integrated technique into his music, and that kindled a new fascination in technique for me: technique did not have to be separate from music; finding the right technique is part of making music!

Theoretically this sounds pretty obvious, but to see André enact this principle in his playing and teaching left a deep impression on me. Even now, as I am learning new pieces, I continue to investigate the way I can relate my physical movements to the shape of the phrase. This takes a lot of slow and patient practice, but the results far outweigh the mindless repetition method I had hitherto been unconsciously using. André’s ghost did not haunt me in my practice in the form of imperative instruction; my memory of the few things he repeated over and over to us, in the funny manner he had of putting them, became a good reminder for what I wanted to achieve in practice whenever I started to stray.

Because of the amount of time we spent together, my studio mates quickly became my…mates. Being the last ones out of class for lunch, we would get a table together, ten or twelve of us squeezing into a table meant for six. We would bond over nerdy piano talk and making fun of André’s antics, which would involve listing out all his “phrases” (“you have the means”, “madame legato is back”, “don’t think about it, just listen to it”, “stop taking things so literally”) as well as imitating all the funny noises he makes while playing the piano (it took me a while to get used to that. I had to hold myself back from laughing on the first day, but by the end of the week it was so natural I couldn’t hear it anymore).

We had a wonderful group dynamic; there was a variety of characters in the studio to keep things interesting. There was Kyra, the kind and sweet American girl who would shriek at ear-piercing decibels when she loses at cards; there was Quang, whose perpetually calming aura away from the piano shatters completely when he places his fingers on the keyboard (my God, what a Franck Prelude, Chorale and Fugue he played!); there was David, who seemed to complain about not being as good as everyone else but actually smashed out a brilliant Brahms 1 and also turned out to be a stellar sightreader; Callum, who is the nerdiest about piano out of all of us and once he gets going about it simply cannot stop. And many more others who made it such a wonderful group to hang out with (if you’re reading this, cheers to you all!).

It was wonderful getting to know everyone’s stories behind the keyboard. At the canteen, I met pianists tackling pieces like Rachmaninoff’s Second Sonata while doing a degree in Maths and wondered what I was doing when I was their age. That was before I met kids ten years younger than me playing virtuosic showpieces while telling me they aspire to be a lawyer when they grow up. There were also “late bloomers” whose unfailing and stubborn work ethic was inspiring to see, as well as pianists who move in the upper echelons of Montreal’s musical circle, telling me endlessly entertaining stories about Dang Thai Son, André Laplante and Bruce Liu etc.

As lessons with André progressed throughout the week, I realized I was learning in a different way from the first week. By listening in on others’ two to three-hour long lessons, I was absorbing André’s teaching philosophy, and so in a way still learning even though I wasn’t doing the playing. I might not be practising as much as I wanted–sitting through five hours of afternoon masterclasses every day meant I had to practise longer hours after dinner and spend less time at the garage–but the amount I learned from those classes was revealed after I left Orford and went back to my own practice room. I must confess, I wasn’t one of the students who diligently took notes and marked scores during the masterclasses; those were the times to sort out the administrative side of my social life. Still, my ears would latch on to important keywords in André’s stream of comments (as well as guttural sounds). To be sure, André’s teaching philosophy wasn’t very complicated and could probably be summed up with two words: phrase everything. Yet, as he repeated these two words to each one of us, I began to see that for him the fundamental thing about music and performing music was very simple. Oftentimes we are the ones who complicate things by adding unnecessary tension, trying to produce a unique interpretation, feeling overwhelmed by all the notes on the page. For playing Beethoven he told us to “sing everything”. For Rachmaninov he said: “don’t try to force the articulation. See how the music is written to fit your hands”. He declared that to play Liszt, “one must believe totally in his way of expression”. These are all meaningful adages to remind us of what is most basic and true in music whenever we stumble into a rut of mindless practice.

Of course, André, being a fantastic virtuoso himself (he could literally play all the pieces brought to him from memory), gave invaluable advice on technique, simple things like “focus on the thumb and index finger when playing chords”. However, ultimately, all of his technical brilliance stemmed from his insistence on “phrasing everything”, and as I saw him play more I realized that he embodied what he taught.

Naturally, having five hours of lessons each day and then spending the rest of it practising or nerding out about music meant not a lot of doing anything else. Spending two weeks in close quarters with other people, I naturally developed crushes on some, but while my roommate had so many amorous trysts lined up he was actually having trouble organizing his practice schedule around them, mine faded into ghosts of fanciful fantasies that eventually dissipated altogether into the musical staves I was staring at all day. Ah, such is the life of a pianist.

At the end of the week, André proposed that the whole class go and get drinks with him. André is a great teacher–his insistence that all his students must try to achieve his musical suggestions is evidence of his faith in all their abilities–but he is loath to stay on his high pedagogic chair outside of his teaching hours. He doesn’t seem to enjoy the prestige that comes with his reputation, nor does he relish the pedestal bestowed upon his feet by his position as a professor. In his lessons, he always reiterated that he was “here to help, not to judge”. Having drinks with André was in many ways just what I had expected it to be like; entertaining to no end. We let him tell all his stories–mostly about his strict Catholic childhood, his time at Juilliard and in Moscow for the ’78 Tchaikovsky Competition–and slowly we got a picture of a very surreal life lived by an intelligent man who much prefers a simple life shorn of pretence and filled only with music, and who therefore finds most people and things around him amusing. We heard of how he was made to kneel behind the upright piano by his first piano teacher who was also a nun, and whom he deemed Sister Holy Chicken Wings; we heard about the pranks he played on a certain Sam Mammel at Juilliard, who was obsessed with the fourth and fifth fingers as well as slurping ramen (Sam Mammel does in fact exist, the only evidence on the internet being a rather rude concert review of his Carnegie Hall Debut); we heard of his worst concert experience in Singapore, where the cumulative experience of a screeching cello solo in the third movement of Brahms 2, the sight of a Chinese grandma eating a banana in the audience and the unexpected realization that he was playing on a “Teinway and Sons” rather than the reputed brand almost drove him to fits of laughter. I would so write his biography if given the chance.

I remember asking him what he would do if he didn’t play the piano. Without hesitation, André replied he would like to be a neurosurgeon. “Or at least have something to do with the brain.” He was fascinated with research and analysis. In a way, he said, practising is like research. Always finding better ways to play a passage, to understand technique and understand the music. “That’s why I love practising so much.” That idea really stuck with me; the idea that practice is a fascination in itself, an intellectual activity, rather than simply a means to achieving the perfect performance.

On my very last night at Orford Musique, we partied hard and drank a lot. I tried–unsuccessfully–to stay up for the sunrise. I was too tired and fragile in the morning to think, but as I returned to London (the one in England) and became once again absorbed into routine and city life, I realized how surreal it was to have spent two weeks in the Canadian mountains studying music with people who love it as much as I do, having to worry about nothing else apart from practising.

Realistically, I probably won’t return to Orford Musique. The North American music scene does not appeal to me as much as the European one, and I far preferred London (the one in England) to Montreal. Perhaps I will cross paths again with the people I met there, perhaps not. But wasn’t it even more precious and beautiful that such a wonderful two weeks will never be repeated again? At any rate, I know that, half a month since, I am looking back on my time at Orford Musique with growing fondness.

Leave a comment