What a wonderful marriage of words and music, of intellect and expression, of ideas and feelings in the third of four concerts as part of the Wigmore Hall “Rachmaninov Song Series” co-curated by pianist and accompanist Iain Burnside and Oxford University Professor of Russian Literature and Music Philip Ross Bullock! The concert was presented alongside a 45-minute lecture by Professor Bullock at 6pm.

It is a marvel to me that I could experience such top-class performances together with probably the most pre-eminent opinion on Russian literature for less than the cost of a sandwich from Waitrose! Perhaps that is not a good sign for the arts in the UK, but I do feel quite happy about this personally. Personally!

I probably wouldn’t have had as much intellectual stimulation had I not gone to Professor Bullock’s lecture beforehand. In his rather entertaining lecture, he spelled out how translation was at the heart of Russian literature, and that while nationalism was strong during the so-called “Silver Age”, a time which produced literary talents like Alexander Pushkin and Dostoevsky as well as musical geniuses like Rachmaninoff, it was a nationalism that fed off of Imperial Russia’s cosmopolitanism. In searching for its own identity, Russia was eagerly absorbing European ideas, sometimes reproducing them even better than the Europeans themselves! And so songs were actually a way of disseminating these translated poetry to a wider audience.

I absolutely felt that, since the way the songs were written, they were almost like speaking poetry, but musically! It was definitely a good thing that the audience was given programme notes with the words printed in both the Russian (in Latin alphabet and not cyrillic) and the English languages, so that we could follow along. The way the composers could shape the music according to the words, or create a whole musical landscape for the poetic image, or enunciate a motif even before its associated words are revealed to us is utterly fascinating to me. It reminded me of reading Shakespeare versus watching the words alongside action on stage; it would all make sense to me when human expression and action were added to it. In the same way, the music not only enhanced the meaning of the words, but added other sense to the words too, multitudinous feelings that are more nuanced and colourful than simply its literal meaning. And this is only the intellectual side of things.

Iain Burnside’s “accompanying” was astonishing in that he was able to lead by basically staying in the wings. Never did he try to cast a shadow on his singers, but if one listens carefully one realizes that he is the one controlling the mood, the tone and the way to poem is realized. Yes, I say that because there was something very intellectual in the way he played, expressive and colourful as it was. He knew the structure of the music very well and was able to shape it the way he wanted to, coaxing the singer along with his deep understanding of the musical form.

It struck me that the Russians were really strong in storytelling and bold in their melancholic emotions, unafraid to appear dramatic and sentimental in their songs. There was something extremely direct and raw about their expression, untainted by concern for formal idealism or decorum. This was of course enhanced by the singers’ incredible voices. I particularly enjoyed the articulate pronunciation of Dmitry Cheblykov the bass-baritone and the directness of his sound, which gave the music the power it needed to produce its dramatic impressions on the audience, but it was Maria Motolygina the soprano’s voice that I am utterly in awe of. When she sang forte in a high register, her voice, so tremendous, provoked in me almost a physical sensation. It was sound that seemed to vibrate in me, and gave off a sensual feeling that left me desiring for more. I must try to articulate this better; it isn’t that her voice was sensuous, it was that hearing her voice–or rather, experiencing her voice–produced a sensuous feeling in me. It was incredible, it was tremendous.

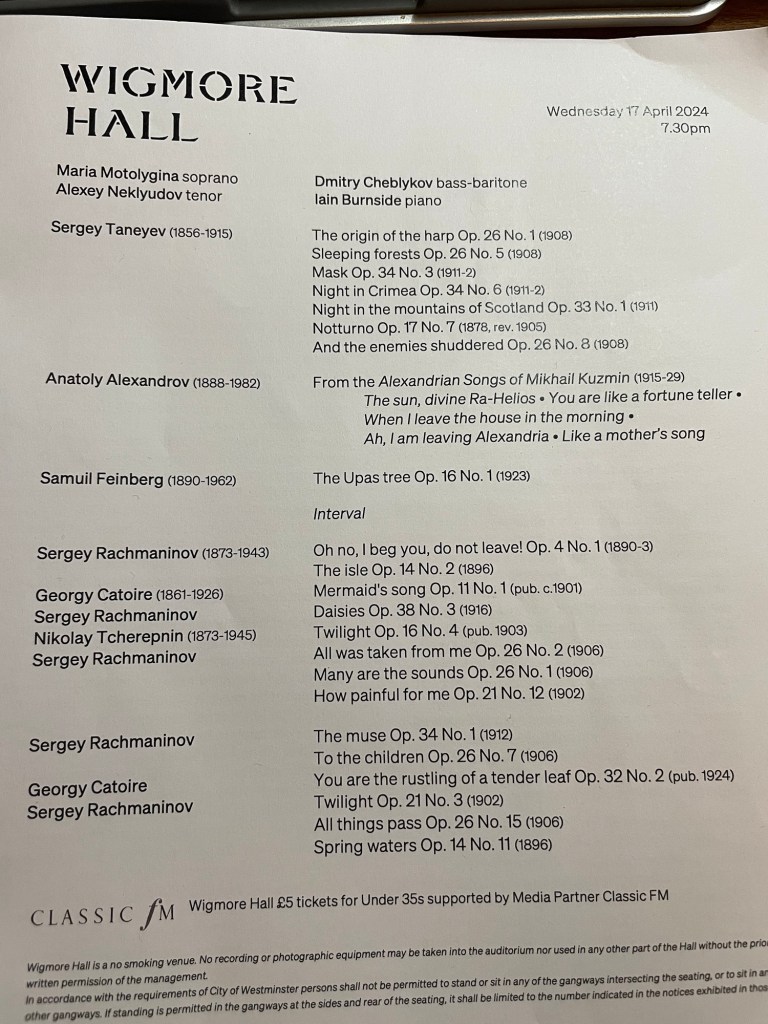

Of course, Rachmaninov’s songs–especially the ones from his more mature opuses–trumped most of the other composers’ included in this concert (the concert was structured so that Rachmaninov’s songs are paired with other Russian composers of the same era) but this format allowed us to experience his music in context, and to comprehend what kind of cultural, musical and literary atmosphere they worked in. It’s like the Tate Modern placing Monet’s paintings among the works of other Impressionists (in fact, this is remarkably similar to the way museums curate exhibitions!). It was also interesting that all of Rachmaninov’s songs were composed before he left Russia for good, as if, as Professor Bullock pointed out, by leaving Russia he had severed that connection. Of course, from his other music, we know he had not, but perhaps there is something even more strongly nationalist in his song settings, something deeply rooted that he could no longer hold onto after leaving his motherland. One can really feel the pain in songs like “To the children” and “All things pass” from op. 26.

For me, someone who doesn’t know a lot about the song literature and repertoire, this concert was definitely a good way to start!

Featured photo credits to Wigmore Hall

Leave a comment