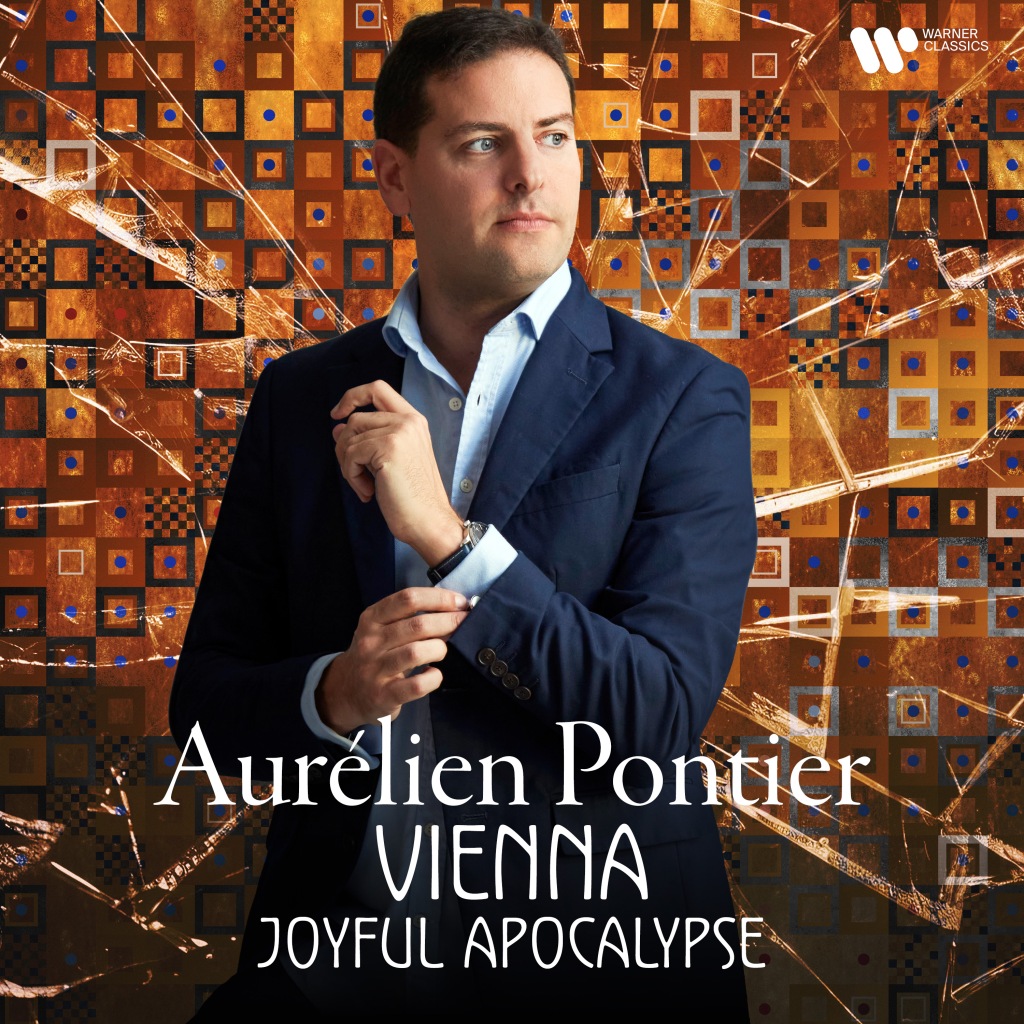

Ahead of his album release for Warner Classics, I had the pleasure of speaking to French pianist Aurélien Pontier about his new album “Joyful Apocalypse”.

“The title is taken from an exhibition put on by the Musée d’Orsay which I visited some years ago,” Aurélien told me. “Artworks from fin-de-siècle Vienna were displayed,” he said, and in fact, the cover art of “Joyful Apocalypse” is very much inspired by the gold-and-glittery style of Gustav Klimt, one of the key artistic figures of Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century right before Europe was imploded by the First World War.

“I am fascinated by Austrian literature during pre-War times,” mused Aurélien as he quoted Stefan Zweig, Robert Musil and Arthur Schnitzler to me. “The mood is very special in the times right before revolutionary events; a burst of creative energy accompanies a sense of impending doom and that is strongly felt in the artistic works created during those times.

“I want to create a logical narrative by putting these musical works together, to paint a picture of what it was like in Vienna at the end of the nineteenth century all the way to the First World War”. Indeed, the album begins with Alfred Grunfeld’s Soirée de Vienne, which is a concert paraphrase of waltz motives from Johann Strauss II’s opera Die Fledermaus, a virtuosic potpourri of delightful tunes and musical fireworks, and ends with Maurice Ravel’s apocalyptic La Valse, the two works bookending a variety of waltzes and salon-style pieces by various composers.

It was interesting that Aurélien did not try to focus on a specific composer in his album, or highlight specific works, as is commonly done in classical albums. Rather, it was programmed to evoke the spirit of a particular time period. In doing so, Aurélien releases classical music from its protected temporal vacuum and calls on his listeners to imagine a different context altogether. Our experience of this album is not limited to the music itself and the performance of it; Aurélien encourages us to interact with the artistic spirit of fin-de-siècle Vienna, as his enthusiasm for novelists and painters of that period suggested to me.

“I came up with the concept of this album during COVID, so it’s been a few years in the making. The whole music industry was basically down during that time, and no one really knew where it was going to go. I read through many pieces during that time, and pieced together this programme.” It’s easy to see why, during that period of isolation, turmoil and uncertainty, Aurélien would gravitate towards the Golden Age in European classical music history.

Nostalgia is indeed a feeling that Aurélien centres upon in his new album, and he sees it as a productive thing. Infused with “anticipatory nostalgia” is how he described the music of pre-World War Vienna in the album’s introductory booklet. Even before disaster struck, there was already a sense of foreboding leading to a yearning for a soon-to-be bygone past, and so beneath all the excessive glitz and glamour there lay something more sinister. This feeling of anticipatory nostalgia is perhaps not entirely irrelevant in the present day. Apart from some Schubert pieces, Aurélien also included many transcriptions of Schubert’s music by composers who came after him, such as Rachmaninoff. Within his album which reminisces on the loss of a culturally vibrant Vienna there lies another layer of nostalgia for another purer Vienna, the one inhabited by Schubert and his intimate Schubertiades. Perhaps we are always constructing idealistic visions in art, and sometimes these creations are refracted onto reality. Viewed in this way, nostalgia isn’t something relegated to the past, but a pwoerful creative force capable of shaping the present.

In a way, nothing is ever lost, Aurélien told me. Humanity does not progress without ever looking back. Mahler’s bursting Romanticism did not give way to Schonberg’s atonal expressionism; they co-existed alongside each other (and in fact both composers feature in “Joyful Apocalypse”). The world may shift a certain way, but there is always value in revisiting music posterity has relegated to the “nostalgic past”.

Aurélien confessed that he has a special affinity to Rachmaninov, who planted his feet firmly in musical idiom considered outdated in his time and yet created music whose value stood the test of time and continues to resonate in the hearts of people around the world today.

And so, with “Joyful Apocalypse”, Aurélien Pontier makes a strong case for nostalgia by presenting a logical and coherent narrative evoking the spirit of pre-War Vienna, painstakingly meticulous in his programme to the point where he even made transcriptions himself (of Schubert’s “An Die Musik” and the famous Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony) in order to shape his musical vision. But in the process of creating such a programme, Aurélien invites his audience to look beyond the music and to really immerse themselves in the spirit of the times.

As Aurélien told me about his process of transcribing the slow movement of Mahler’s Symphony: “I added almost nothing onto the orchestral score, and I play the music at a much slower tempo than most pianists who play other transcriptions of this movement. I want my audience to listen to the space between the sounds. Sometimes that is where the real meaning of the music can be found.”

“Joyful Apocalypse” will be released on 31 May by Warner Classics, available on all streaming platforms as well as in physical copy.

Track list:

- Alfred Grünfeld Soirée de Vienne, Op. 56 (Paraphrase on Waltz Motives from Johann Strauss’ Die Fledermaus)

- Leopold Godowsky Triakontameron: No. 11, Alt Wien

- Otto Schulhoff 3 Bearbeitungen nach Motivenvon Johann Strauss, Op. 9: No. 2, Pizzicato-Polka

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Polka de W.R. (After Behr’s La rieuse, Op. 303)

- Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky 6 Pieces, Op. 51: No. 6, Valse sentimentale

- Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Valse-Scherzo, Op.7

- Fritz Kreisler 3 Alt-Wiener Tanzweisen: No. 2, Liebesleid (Arr. Rachmaninoff for Piano)

- Franz Schubert An die Musik, Op. 88 No. 4, D. 547 (Arr. Pontier for Piano)

- Franz Schubert 12 Waltzes, Op. 18, D. 145: No. 6 in B Minor

- Franz Schubert Waltz in G-Flat Major, D. Anh. I/14 “Kupelwieser-Walzer”

- Adolf Schulz-Evler Arabesken über “An der schönen blauen Donau” (After Johann Strauss’ Op. 314)

- Franz Liszt 4 Valses oubliées, S. 215: No. 2 in A-Flat Major

- Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 5 in C-Sharp Minor: IV.Adagietto (Arr. Pontier for Piano)

- Arnold Schönberg 6 Kleine Klavierstücke, Op. 19: No. 6, Sehr langsam

- Maurice Ravel La Valse, M. 72

Leave a comment