Yesterday was my first time back at the BBC Proms this year, the annual summer classical music festival hosted by the UK’s official radio station at the Royal Albert Hall. It’s always nice to see classical music being performed in less formal settings, and the BBC have done well in their programming, introducing new music in concerts while also bringing in big names, thus drawing a crowd to premieres of contemporary pieces.

This can definitely be said for yesterday’s concert, which had quite a large crowd, mostly East Asian and probably followers of Seong Jin Cho, who performed Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, “Jeunehomme”, under the baton of Sakari Oramo.

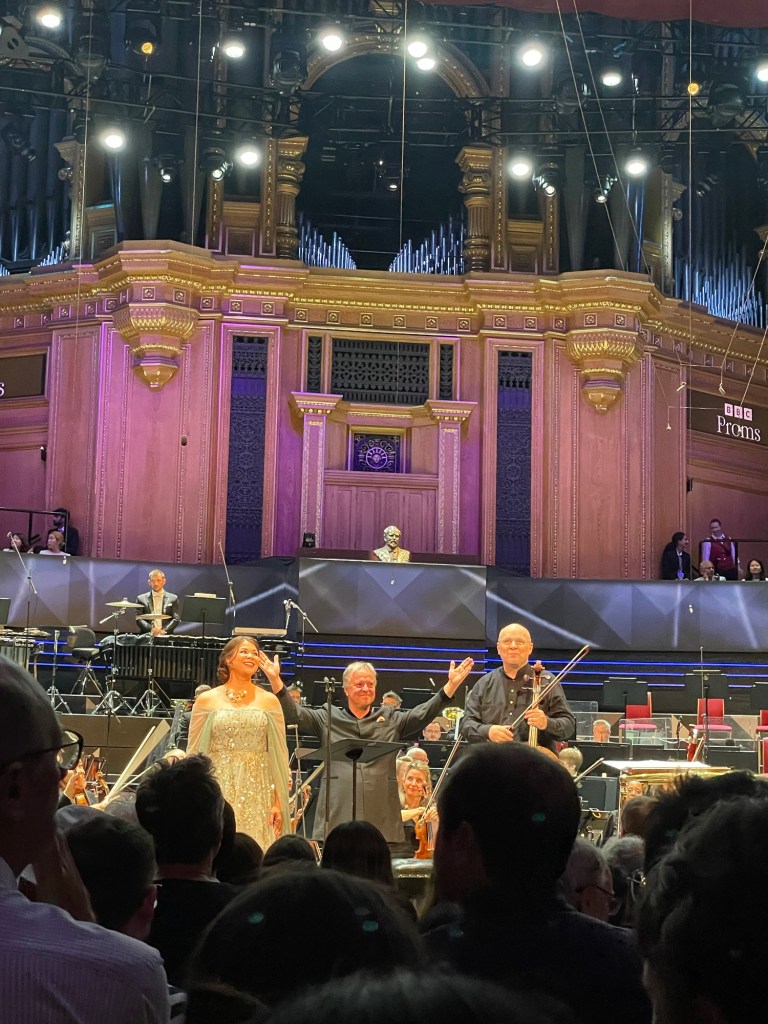

The piece which opened the concert, however, was the late Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho’s Mirage, written for cello, soprano and orchestra. The soloists were cellist Anssi Karttunen and soprano Silja Aalto, and in fact Karttunen was one of the performers the piece was originally written for.

The twelve-minute piece was inspired by the famous trance states of shaman Marla Sabina from southern Mexico in the 60s, who apparently achieved these states with the aid of “magic mushrooms”. Her chants were recorded, translated into English and set to music by Saariaho. They are not the most inspired or profound words (“I am the Lord eagle woman; I am the woman who swims” etc.) but in the case of Mirage the music is more important than the words.

Having come across Saariaho’s music before (I attended a performance of her opera Innocence put on by the Royal Opera House last year), this piece certainly has the Saariaho stamp on it: mystical and rather dreamy with a tinge of uncanniness. I wasn’t especially drawn into the sound world at the beginning, but Silja Aalto was wonderful in taking the audience with her, showing us the direction of the music’s narrative. Eventually I began to see how the music is structured, and how certain chords are stacked together to create the mysticism in Saariaho’s music. Aalto was incredible in heightening the drama and shaping the narrative, so I owe a lot of my understanding of this performance to her.

Seong Jin Cho’s performance of Mozart’s ninth piano concerto, nicknamed “Jeunehomme”, was for me the highlight of the evening. I’ve heard Seong Jin Cho live a few times now, but never playing Mozart, and last night made me realize how suitable he is to performing Mozart’s music. Never losing his cool composure in his suit and tie, his playing had real “main character energy”; not in the sense of announcing himself with force, but a more subtle sense that he knows once he quietly sits at the piano everyone in the room will fall silent and listen, and indeed listen we did.

Even with the terrible acoustics of the Royal Albert Hall, Cho’s light touch at the piano made me want to hear more and more. Despite being note-perfect, there was hardly a sense of laboured perfectionism, but everything seemed to be conjured spontaneously. The pianist, relaxed and enjoying the attention, is able to relax completely and draw from his infinitesimally nuanced palette to paint melodies sometimes richly coloured, sometimes sweetly fragile, always in happy communion with his audience. Cho did not have to force his way through the orchestra; his creativity and beautiful sound made all want to listen to him. I imagine him smirking on the inside, gliding over the keys in blissful freedom knowing he has his audience trailing by his coattails, something Mozart must have felt back in the day.

Despite everything being effortless to him, Cho never made it feel as if this music was beneath him. There was a very enticing quality to the creativity and freedom he demonstrated in his performance last night, and it served as a reminder that great pianists aren’t merely people who labour tirelessly at their craft, but also people who can have a great time onstage and in doing so, inspire their audience.

Now I have never heard Strauss’ monumental Alpine Symphony live before, and had been very excited to see last night’s performance. However, it was rather underwhelming, notwithstanding the fact that I had to stand rigidly for the entire 45 minutes of it (#prommingproblems). Perhaps it was the dry acoustics of the Albert Hall that didn’t allow for the sound to sustain, which made a lot of the grand moments a bit of a problem. To me it just seemed like barrages of sound spread throughout the good part of an hour, linked together by fluttering trills or wind solos. The occasional brass choir situated in the “heavens” of the Hall, the wind machine or banging tins piqued my interest momentarily, but was unable to sustain my attention. There wasn’t much structure to hold my attention, and the idiosyncratic “Strauss sound” at times seems a little over-the-top and dated. Neither did I feel that Oramo was fully committed to this uber-Romantic idiom; he seemed too orderly for this over-the-top Romantic expression.

Perhaps in a better Hall where I was actually seated I would give this performance a better review. Perhaps.

Post featured photo credits to the BBC.

Leave a comment