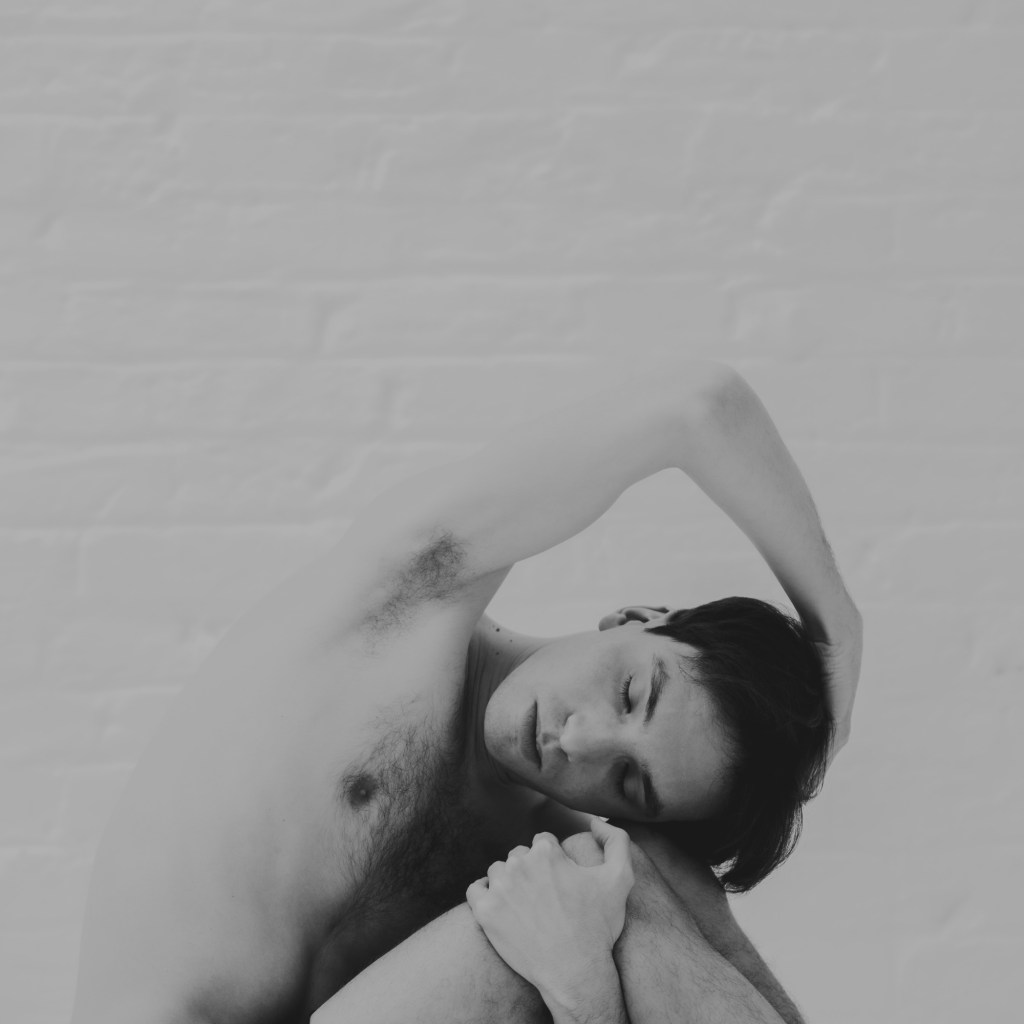

Pictures of a half-naked Jonathan Ferrucci in different poses and positions pepper the walls of St John the Baptist Church in Wimbledon.

These are the fruits of a creative collaboration between pianist and yogi Jonathan Ferrucci and photographer (and sometimes cellist) Matthew Johnson surrounding Bach’s timeless Goldberg Variations, presented at the Wimbledon International Music Festival.

A little booklet was distributed in which 32 photographs of Jonathan in different poses are subtitled with each of the 30 variations, as well as the Aria which is played at the beginning and at the end but which, as Jonathan noted at the post-concert discussion, “sounds completely different”.

Each photograph being planned, enacted, shot and edited to correspond to the artists’ conception of each of Bach’s variations, we of course not only hear the performer’s interpretation of Bach’s music, but also appreciate a visual interpretation of the music through the camera lens.

Having heard the Bach’s Goldberg Variations live multiple times, I am still surprised at how much difference an artist can make to this grand master’s music, especially under the fingers of someone so long immersed in Bach’s music as Jonathan.

Looking at Matthew’s photos as I listened to Jonathan’s performance did not distract me from the music, but added to it, giving it a personal and contemporary shade, bringing it closer to the individual and away from the untouchable divine that Bach’s music has often been—I believe—erroneously associated with.

I have experienced cross-arts collaboration on Bach’s Goldberg Variations before, in the form of a live collaboration between pianist Pavel Kolesnikov and dancer Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, but there exists a tension between capturing dynamic body movements with photography, an art form that is by nature static. This is further contrasted by listening to music, an art form that can only reveal itself through time. The interpretation of music through photography can only be abstract and not literal, and so as audience we are compelled to fill that gap with our own imagination, which is perfect with music that is simultaneously vague but also intensely personal as Bach’s music. The two art forms—music and photography—complemented each other without stepping on the toes of either.

I say all this without detracting from the fact that Jonathan’s performance of the monumental Goldberg Variations was masterful and unique. Even with a rather resonant acoustic and a large modern Steinway where the bass is a lot more muddier than the middle and top registers, Jonathan plays as if with two right hands, so clear was his articulation.

What I found most impressive was the space he could find in the music. Everything was so thoroughly understood it seemed he had the music in front of him and he could select what he wanted to pick out of it. His hyper-vigilant fingers were constantly aware of every voice and that Bach’s music was an organic intertwining of vocal strands, and as a pianist he was like an expert puppet master who only had to tug slightly to bring a certain voice to the fore in a repeated section to shed a completely different light on music we thought we already knew.

I also loved that everything Jonathan did was intentional and deliberate. Bringing to the table his deep understanding of Bach’s music, he knew how to add ornamentation in a way that brings the music to life or shows it in a different light. It did not have to be excessive; sometimes all he had to do was change the articulation slightly and already everything felt different, and those subtle moments were absolutely delicious. Other times, he would add inventions of his own, such as the sostenuto pedal to highlight a certain voice in the repeat of variation 20, or virtuosic semiquaver passages in variation 22 to completely change the character of the music, or prolonged trills in variation 24 to make the music more expressive.

He was not one to shy away from the emotional expressiveness of the music by drawing on the power afforded by the modern Steinway too, as shown by his extremely intense and powerful ending to the great, tragic G minor variation 25.

This performance and collaborative project on Bach’s Goldberg Variations once again showed just how much scope for personal interpretation there is with classical music, how much Bach’s music can be great and personal at the same time, and that creativity, when matched with thoughtful study and deliberate intention, can yield fruitful results worthy of great works of art.

Photos of GOLDBERG, the collaborative project between Jonathan Ferrucci and Matthew Johnson, were given to me with the permission of Jonathan.

Leave a comment