A few weeks ago I came back from the beautiful city of Valladolid in Spain, where I participated in the 2025 Frechilla-Zuloaga International Piano Competition. I spent a whole month preparing for the competition intensively, but unfortunately things did not go the way I wanted it to and I was eliminated after the First Round.

However, surprisingly I did not feel too disappointed. To be sure, this was not my first international competition–I had done a few back in the UK–but this was my first proper one abroad, a three-round competition where the final round is a concerto performance with the incredible Castile and León Symphony Orchestra. This was not some provincial competition–most frequently found in Italy–where anyone could enter as long as they paid an application fee, organized their own accommodation and which, upon arriving, competitors realize they have to fight for battered upright pianos in small classrooms to practise on. No, I was one of 21 selected participants, accommodation and breakfast was provided for us, practice slots were ample and pianos were in great condition. I mean, we played in the beautiful Symphony Hall of the Miguel Delibes Cultural Centre! It was amazing, really.

From past traumatic experiences at all sorts of competitions, I was determined not to repeat past mistakes. Here are a few things I did to prevent history from repeating itself:

1. Using old repertoire.

In the past, I had made the mistake of not only including new pieces in my competition, but actually learning some right up until competition week. To be fair, I wouldn’t have done differently since I used to view them as a way of forcing myself to learn more music quickly, but not being prepared for one piece of music in one particular round–no matter how short the piece–can actually affect my performance in other rounds, since I would be worrying about the new piece and spending more time practising it rather than evenly distributing my practice for all the rounds.

This time, none of my repertoire was new. By now, I have some “competition standards” under my belt: I use the same E flat major Bach Prelude and Fugue from the Well-Tempered Clavier Book I in literally every competition that asks for a Bach Prelude and Fugue. My go-to classical sonata is Beethoven’s “Les Adieux” Sonata, a succinct but virtuosic piece that’s always effective, although I do find it quite difficult and uncomfortable and am looking to swap it out soon. Rachmaninov’s Second Concerto is by far the concerto that I’ve played most in competitions, but unfortunately I realize I’ve stopped learning concertos and will have to add a few more in the coming year to my repertoire.

Franck’s Prelude, Chorale and Fugue I learned only two summers ago, but have played it countless times and can probably play it in my sleep.

The only unfamiliar piece is the Chopin B minor “octaves” etude and the Scriabin etude op. 8 no. 12. The Chopin etude I had learned two years ago but never felt comfortable enough to bring it to any competitions; the Scriabin I played in a competition for the first time in May, but don’t think I quite pulled it off. I have played it as an encore a few times since and it’s grown on me.

2. Performing the pieces publicly and privately a few weeks prior.

Runthroughs are essential.

When preparing for competitions in the past I used to get into the mindset of being note-perfect. That would mean working on a piece endlessly trying to make sure I can play it through without a single slip. There are pianists out there who can play the most complicated etude perfectly without dropping a single note, but that’s not me and trying to be that just a few weeks out from a competition is a grave mistake.

Not only that, the stress of trying to play perfectly would get to me when playing onstage. My playing become rigid and unmusical, and it would actually lead to more mistakes!

This time I made sure to perform the pieces as much as I could publicly or to a friend before the competition. I was notified of my selection only a month before the competition. I had been working on new repertoire then, but I dropped everything and changed my programme for some scheduled recitals to fit my competition repertoire as best I could. I also made sure to run through the concerto with a friend a few days before leaving for Spain.

This was to ensure my perfectionism didn’t kick in again and tempt me into locking myself in the practice room.

Some of the pieces I had to pick back up incredibly quickly for the scheduled recitals, so they weren’t as well-prepared as I’d have wanted them to be, but performing them live in a less-tense environment than a competition allowed my body to remember the feeling of playing those pieces, and I actually discovered new things musically while performing them that I later brought to the drawing board in preparation for the competition.

Not having a grand piano at my regular disposal, I also made sure to get opportunities to practise on different grand pianos as much as I could before the competition to get used to the touch, in case my fingers started atrophying.

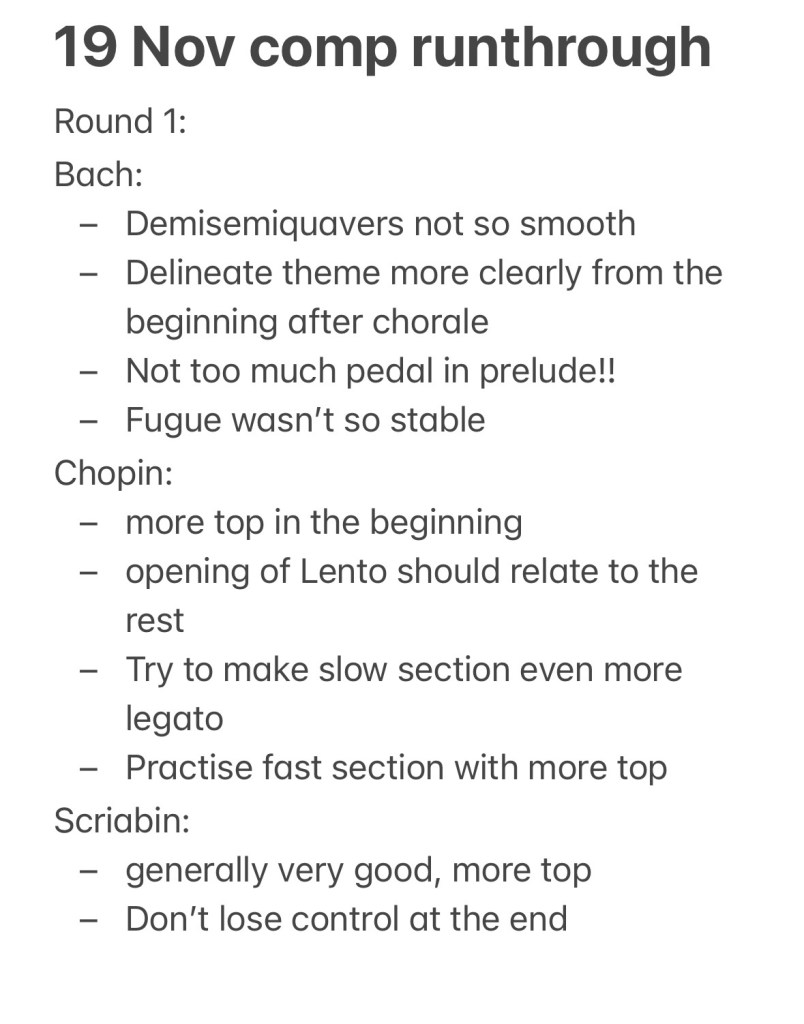

3. Recording my runthroughs and listening back to them.

This is actually my first time preparing for a competition without the help of a teacher. With no one to give me guidance–and I believe with those pieces I no longer need extra advice–I must follow my own ears and conscience.

I always hated listening back to my own performances because I thought everything should be left in “the moment” where they belong and not be scrutinized afterwards in a cold and analytic manner, but I realize it’s just my own egotism.

Listening back allowed me to pick up on things I wasn’t able to “in the moment”, which you could then correct. Surprisingly, it also helped me appreciate the spontaneity that live performance brought to my playing. There were certain moments I did in performance that I did not do in practice, but which listening back allowed me to “store” for future use.

Of course, the danger of listening back is being too analytical and then correcting your playing as if you’re “ticking boxes”. So in the final few days before the competition, I ran through pieces without recording just to remind myself of the feeling of playing those pieces without the burden of “correcting mistakes”.

4. Arriving with plenty of time to spare.

At Valladolid, I met a competitor who had just flown in from New York and who unfortunately drew the short straw of playing first. He just shrugged and told me, “that’s the way of life for an actual concert pianist”.

What he said was true. As concert pianists, there are so many factors we cannot control that can affect our performance. Unfortunately, as much as I want to be, I am not a very spontaneous person. I like things under control and I like to feel in control. So the things I could control, I did. Arriving on time is one of them.

Even though the conference to announce the beginning of the competition was on Sunday evening, I took the early morning flight from London (cheaper too!) and tried to be there by late afternoon. Good thing too: Sunday in a small European city means everything is closed; I even had trouble finding a taxi as there was no Uber! I got there, took a nap, and felt refreshed as I went out to meet people. Arriving with a good mindset is important to me, and not feeling hurried or hectic most definitely helps.

5. Getting a good night’s rest.

There was a time when I arrived at a competition in Italy having to play a Chopin etude and a Scriabin sonata at 8am in the morning. That experience scarred me for life. There were also many times where I arrived at a competition area the day before to give myself time to get used to the place, only to have trouble falling asleep, whether it be because of paper-thin hotel walls, stress or unfamiliarity of surroundings. Insomnia is the WORST thing you can get before an important performance.

For me, being able to relax helps with this. I brought my earplugs along, made sure to turn off devices early on in the night, read a book or my scores before bed, and went to bed at a slightly earlier time. Not too early; just slightly.

6. Not treating it as a competition.

Perhaps the most important thing I learned from my past competition experiences is how to view the competition experience itself. I personally find it more freeing musically when I see it as a performance opportunity. I tend to perform much better in competitions where I did not feel like I was being judged, but where I felt like I was performing and sharing what I love. When I think about being judged or compared against others, I start to clam up, and natural musical expression cannot flow in that state. That was why I told myself that no matter what, I would treat the preparation as I would a competition, but treat the actual performance as what it really is essentially: a performance.

In the end, even if I did not get through, I would feel much better about having performed rather than having safely delivered.

Rather than focus too much on my own playing, I tried to absorb my environment in a positive manner: appreciating the city, its people and its food; meeting like-minded contestants and having nice conversations with them; enjoying the beautiful hall; going to the opening gala recital and being awe-struck by the head of jury, Alexander Gavrylyuk’s jaw-dropping performance; seeing it as a chance to play for and connect with world-class, established pianists who form the jury. All these things helped to form a positive mental bedrock for my performance, which I was determined to enjoy, whether it be a 12-minute first round programme or a full concerto performance.

Of course, it’s easier said than done. These are all things I did and strategies I developed through countless failures and traumatic experiences at competitions. I still make these mistakes as it’s hard to simply stopper very human feelings like anxiety and fear, but I can see that I am getting better at managing them and channelling the stress into something more productive and even growth-inducing for myself.

I also made a note of making the most out of this competition, and that meant seeing the competition for what it is, not simply going in, playing my bit, then leaving the stage feeling depressed, going back to my hotel room and binge-watching Netflix.

This time, I attended all the events around the competition such as the conference, the opening gala recital, sat through almost half of the First Round performances, talked with people and tried to get jury feedback after my performance. Through that I learned a lot more than I would have if I had simply come to play a few minutes.

I shall dedicate the next part to my observations of this competition and how it relates to piano competitions in general; how they differ from performances and what I’ve realized is most effective in competitions. You can read it here.

Lessons from a piano competition part 2: observations

In my previous post, I talked about what I did to prepare for the 2025 Frechilla-Zuloaga Competition based on what I learned from previous competition experiences. But it wasn’t just about things I changed leading up to the competition; I also made sure to observe the competition itself. A standard, high level piano competition normally…

This is not to say it applies to ALL piano competitions. In fact, all competitions are different; they are of different scales in terms of size and prestige; they have different grading and voting systems; they have different organizational methods and even different agendas sometimes. However, I do believe the nature of competitions means that certain aspects are similar across the board and I believe what I have identified in THIS specific competition could also apply to many others, especially those of a similar scale.

Leave a comment