I was lucky enough to spend most of my summer practising on grand pianos at school and listening to concerts given by great artists at the café I work at; one would consider that a summer immersed in classical music. But nothing quite prepared me for the experience of spending four days at the Chetham’s piano summer school. It was one of the most intense, yet also most inspiring, experiences I had with classical music.

As I collected my itinerary and started unpacking my stuff in the shabby room in the boys’ boarding house, I had no idea I was going to spend the next four full days oscillating between perpetual exhaustion and elation. Now I wonder, looking back, whether it is because of the constant tiredness which heightened the emotions I felt when listening to performances. In any case, I must try to articulate why I felt those four days of constantly living with music seemed like an alternate reality.

Day in the life

My daily schedule went something like this:

7.30am wake up and breakfast. 9am practice.

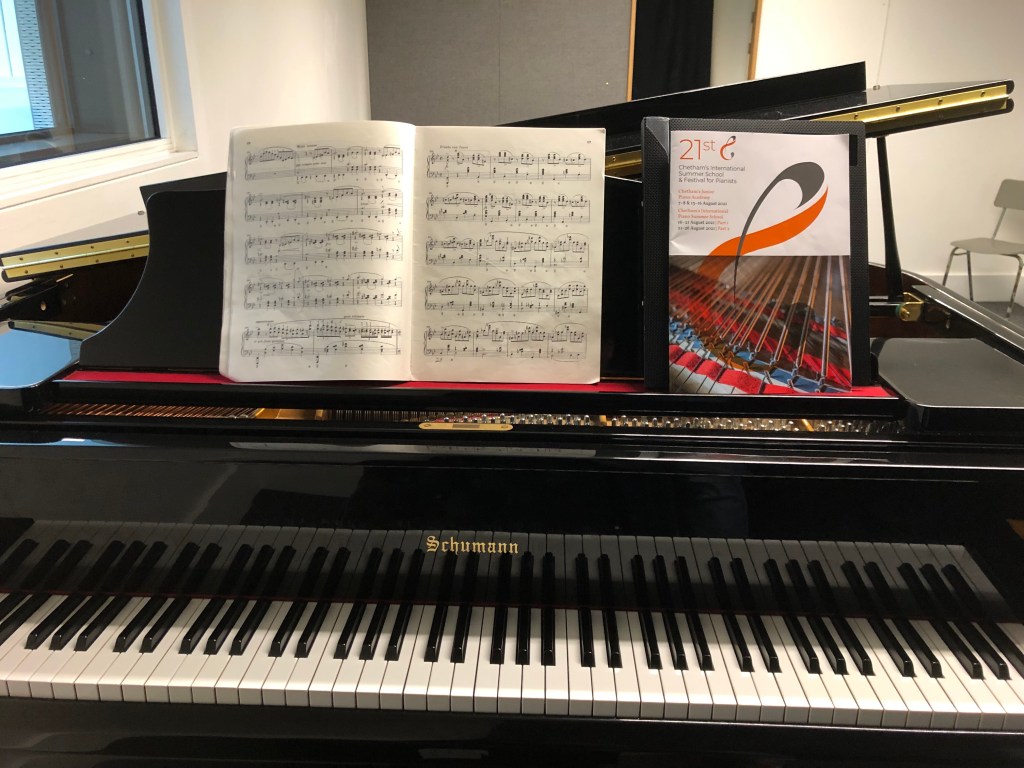

I was one of the fortunate ones whose lessons were never scheduled at the ungodly hours of 9 or 10am. I always had ample time to practise before a lesson. Unfortunately, morning is the time when everyone is most motivated to practise, and so I always ended up with a Yamaha upright.

Practise until 11 am, then steal a grand piano room while the others went on coffee break (the coffee served was decaf, so I quickly decided it was not worth my time).

Lunch at 12 or 1pm, then there would be a young artist recital until 2.30pm. This would be around the time I get a lesson. If I didn’t, this would be a good time to take a much-needed nap in preparation for the evening ahead. Otherwise, I could sit in on others’ lessons and observe some of the greatest teachers in the country in action.

After dinner, at around 7pm, there would be the first concert of the evening, given by a faculty member. A small break would ensue, followed by a second concert at 8.30pm. By the time the second concert finished, at around 10pm, I would be bursting with inspiration, so much that I had to grab a bottle of Peroni at the bar and let it all out on the equally enthusiastic summer school participants around me. Student concerts in smaller rooms followed the concert hall recitals, and would go on till midnight. By the time I had finished listening to the last performance, the first concert of the evening would feel like it had happened the day before. That would mark the “official” end to a day, but most nights, with a few beers inside me, we would end up playing around on the pianos, improvising, sightreading two-piano works, or simply rhapsodizing–with words–on how great Bach’s music is. Bed time was usually past 1.30am, and then the next day I would start all over again.

A world of its own

On paper, this just sounds like a very intense music camp, but when you are immersed in this little world within Chetham’s, music becomes a different experience altogether. Even though the dynamic city centre of Manchester was only minutes away from Chetham’s gates, it felt like a different world altogether while I was there. It was a fascinating city to marvel at, like an aquarium, but it was not one to immerse myself in. I walked its roads only to get post-practice coffee or an occasional helping of actually edible food, but the city itself was inconsequential to me, totally disconnected from the world of Chetham’s summer school.

It was in this little world, where music was a way of life, that I felt my view of music changed. Okay, maybe I’m being a little dramatic, but those four days went a long way to jolt me from some of the habits I had been making in my practice up till then. This is not to say I felt my technique suddenly improve; four days aren’t enough to work that sort of miracle. However, I believe a change in my mindset can do so much to change my playing.

Living with musicians

We normally see great pianists clad in magnificent tuxedos or sparkly concert dresses. We see them beaming triumphantly after playing Rach 3, facing a sea of standing ovations. They are larger-than-life, sometimes mythical to those of us who have to scrounge £10 tickets to sit in the stalls of the Royal Albert Hall and view them from afar.

At Chetham’s, I saw Peter Donohoe, one of the legendary English pianists and laureate of the Tchaikovsky competition, holding his tray of schoolfood in the canteen looking for a seat. I saw Joanna MacGregor getting her morning coffee at Caffe Nero. One of the contestants of the prestigious Leeds Piano Competition lived next door to me, and had such trouble hearing his alarm he asked me to wake him up every morning.

At Chetham’s, we were all thrown into the same situation, performers and participants alike. It was strange to see people whom I have heard so much of walking around me talking about the weather. It was equally unsettling to see some normal guy I was having lunch with suddenly appear onstage the same night and perform one of the most inspiring recitals I have witnessed.

But it is precisely this aspect of music-making–to be living in close proximity with musicians–that changed my way of looking at music. Seeing them as normal human beings made their performances seem much more intimate. Yes, there were hiccups here and there–an untuned piano, a memory slip etc.–but that is only human, and the more I am able to accept the human aspect of music-making, the more I am able to appreciate the power of music. I think this goes both ways (though I am yet to set foot on the stage of Stoller Hall); the more the performer is able to feel at home in the performance environment, the more he or she is able to give a better performance.

The other thing with living with musicians is that I can see how their personality translates onto the stage. Now, this is of course generalizing, because one’s personality cannot be summed up in one performance, nor can one fully equate the performer’s onstage personality to their offstage personality. But my point is that living with musicians allowed me to see that personality does very much affect performance. When I have to pay to go watch concerts, and when the only glimpse I have of them is their moment onstage, I tend to focus on the performance, not the performer. I think: ooh, this bit seems a little too fast, this bit I wouldn’t play like that. Post-concert, I reflect on the enjoyability of the concert; how does it feel to me. Am I getting my money’s worth. In that sense, I am a self-centred listener.

But hearing so many performances back to back at Chetham’s, and also seeing the performers in real life, I began to gradually see how a performer’s personality informs the musical choices they make. To give a few examples: Joanna MacGregor is a real showman when it comes to piano playing. Probably influenced by her engagement with Latin American music and tango especially, genres of music which are much more extroverted and audience-engaging than the introspective nature of Brahms or Schumann’s music. Her playing has a very performative flair which captivated us all that one night she played a programme of mainly Piazzolla’s music. In contrast, Benjamin Frith showed his contemplative and introspective nature in the way he revealed the subtleties of the piano’s palette in his programme of Brahms, Scarlatti and Mendelssohn. Murray McLachlan showed himself as a real storyteller in the way he confidently handled his all-Russian programme and in his ability to handle long, dramatic tensions while tackling those virtuosic pieces. These performances were all very different, but all equally inspiring. It’s not that so much they consciously choose to play a certain way; it’s more their personality compels them to play in a certain manner. I may like some performances and dislike others, but there is no right or wrong. However, I believe the difference between a performer and a student lies in personality conveyed through performance. A good performance should always convey personality. The human element is what makes music elevated.

Living with music

A performance is never great simply because the music is great. It is great because the performer makes it so, but the greatest performance is one where the performer creates the illusion that the audience has an unmediated access to the music. It was when I heard Henry Cash’s performance–he was one of the participants–that I realized how genius a piece of music Chopin’s “raindrop” prelude is, where the repeated notes carry on throughout the whole piece, tying the exquisitely beautiful melody with the sombre, chordal middle section together. Peter Donohoe’s performance of Haydn’s last piano sonata reminded me of how light-hearted Haydn’s music really is. Thomas Kelly’s performance of Thomas Adès’ Three Mazurkas revealed to me the innovative ways this contemporary adapted the model first established by Chopin. Great performances are the ones that inspire me to look at the music with a different eye. They make me want to learn the pieces myself.

These performances are different from student performances because they appear so natural. When the performers get to the piano, you feel that they want to speak the music, to play the music as they mean it. The only way to do that is to really know the music. And so, while on the surface such performances may appear effortless and natural, I know that a lot of work went behind them to create this appearance. Hours of practice, technique drills, memorizing, changing fingerings. Still, the core of what makes it an artistic performance rather than a student performance is that they understand the music and know what they want to say when they are playing the music. Recently I’ve been spending a lot of time in practice rooms trying to learn repertoire, but when I played for the teachers at the summer school, I realized a lot of times I was merely trying to get through the piece rather than actually knowing what I want to say about it. I decided to step back a little bit and do some score-studying in my room. Lo and behold, I went into a practice room knowing what I actually wanted to work on. I felt my passion for the music rekindle, and as I played the Chopin ballade no. 1 for one of the teachers, I felt the joy of playing such a wonderful piece of music again. It was the joy that made me play better than I did in practice.

I know what I have just said sounds incredibly clichéd. Everybody knows that music played without feeling is not music at all. But I think it’s seeing incredible musicians do what they do on a daily basis that made me understand that there is so much more joy in living with music, getting to know music, than there is in practising in the hopes of playing a good performance. It’s probably why I felt so much more inspired by the performances than by the time I get to spend on practice at Chetham’s (not least because I spent most of my practice time on uprights!). There is something very inspiring about living and breathing music–which is what many of the performers I encountered did–than simply playing piano.

Perhaps I am romanticizing things, but I definitely felt that I briefly lived in a reality suspended slightly above normal life during those five days, an experience which has created a deep impression that I hope will last as I return to London and resume my daily routine of watching Netflix while I practise the piano.

Music and people

I’ve said a lot about the human element in musical performance, the personality, blah blah blah. The reason I had such a great time at Chetham’s was because everyone around me loved music, and loved playing piano. Enough to pay a fee to travel somewhere and be locked up in a boarding school with other piano nerds. Sure enough, I had a great time talking about music and playing music with them. My best memories are definitely the nights I spent with some other participants playing on the pianos in a practice room after the evening concerts, improvising, accompanying concertos and jamming while having some beers.

Oh, I will be Bach next summer for sure.

Leave a reply to Ed Walters Cancel reply